I’m most interested in how genetic factors and environmental variation combine to shape the development of organisms, and what this means for their evolution.

I take an integrative approach to these questions, relating changes at the level of gene sequence, gene expression and protein abundance to variation in development and life history (the patterns and timing of key events, including maturation, reproduction and senescence). I compare individuals, populations and species, generally considering these effects across different environmental conditions.

Fitness effects of transposable elements

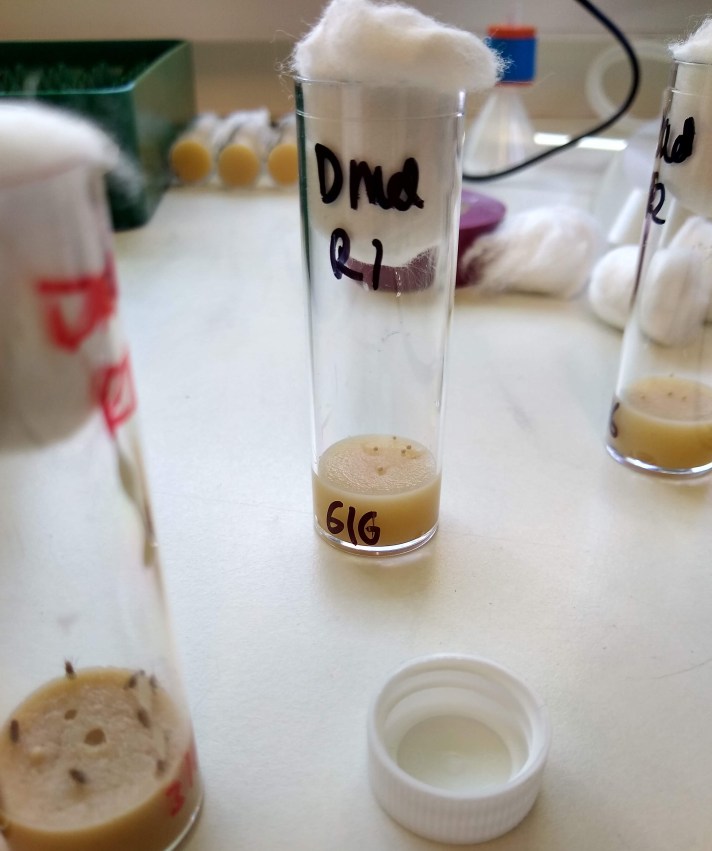

Transposable elements (TEs) are selfish genes that are able to replicate independently of the host genome (all the genetic material in an organism), and insert themselves into new parts of the genome. TEs are abundant in almost all multicellular organisms (e.g. accounting for up to 44% of the human genome), and the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster is no exception (where TEs account for roughly 20% of the genome).

In this project at the University of Liverpool I combine molecular biology and bioinformatics to assess variation in TE insertions between lines of flies, and relate this variation to fitness consequences such as development time and reproductive success.

Impacts of environmental stress on marine mollusc populations

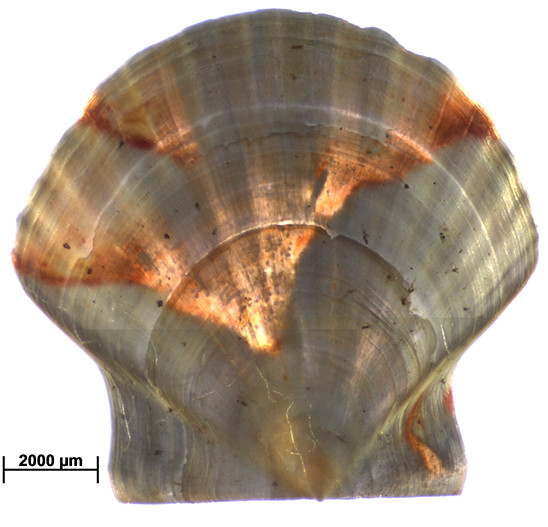

Increasing CO2 in the atmosphere is a major driver of environmental change in the ocean: global warming leads to not only to elevated sea surface temperatures but also acidification of sea water. During a fellowship carried out between Ifremer and the University of Brest in France I investigated how these climate stressors influenced the growth and physiology of the great scallop Pecten maximus, comparing hatchery-reared juveniles from two different European populations: Brest, France, and Bergen Norway

Although the populations are genetically distinct, we don’t know whether they will differ to in their response to changes in the marine environment. To understand how populations differ, and more importantly, how they might respond to future climate change I carried out controlled laboratory experiments, integrating phenotypic, eco-physiological and proteomic approaches.

Developmental plasticity and its evolutionary consequences

The way that organisms develop their phenotype (their characteristic features or traits) is shaped by the interactions between genes and the environment. Many organisms are sensitive to environmental variation and will develop different phenotypes in response to changes in the environment (‘developmental plasticity’). How a developing organism perceives and ‘integrates’ this information not only alters that individual’s phenotype but also has consequences for our understanding of evolutionary processes.

During my PhD at the University of Liverpool I studied the consequences of variation in these interactions using the water flea Daphnia. This small crustacean is ideal for investigating gene-by-environment interactions because it often reproduces asexually, allowing many genetically-identical individuals (clone lines) to be grown in different environmental conditions. During a number of different experiments I found that integration of different environmental signals by developing Daphnia varied dramatically between different clone lines and was a key driver of phenotypic variation in important evolutionary traits such as age and size at maturity and number of offspring.